Why does AI require African input?

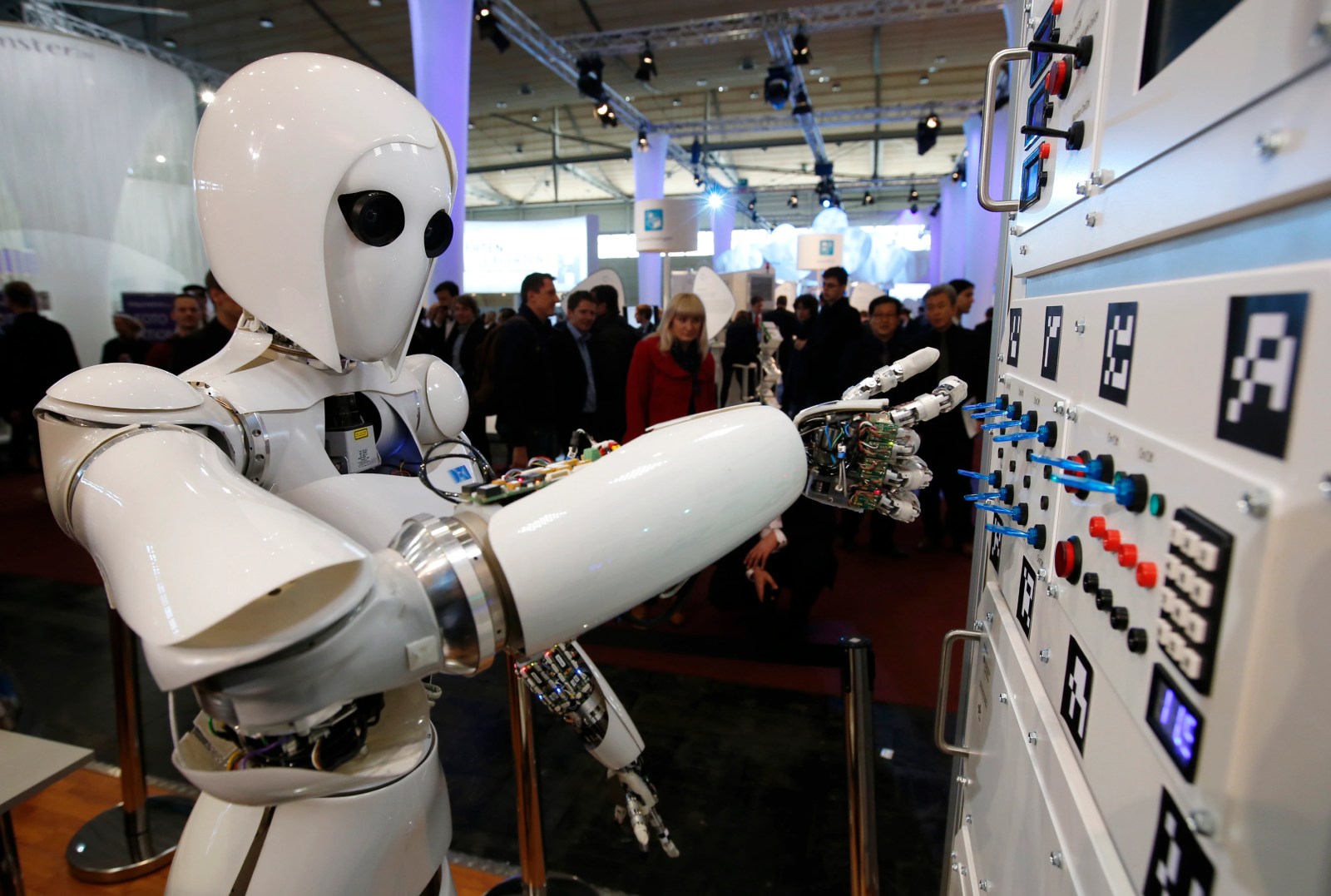

Once upon a time, artificial intelligence (AI) was the stuff of science fiction. However, it is becoming more common. It is employed in mobile phone technologies as well as automobiles. It powers agricultural and healthcare tools.

However, questions have been raised concerning the responsibility of AI and associated technologies such as machine learning. Timnit Gebru, a computer scientist with Google’s Ethical AI team, was sacked in December 2020. She had previously warned about the social consequences of prejudice in AI systems.

For example, Gebru and another researcher, Joy Buolamwini, demonstrated in a 2018 publication that facial recognition software was less accurate in identifying women and persons of color than white men. Biases in training data can have wide-ranging and unforeseen consequences.

There is already a considerable corpus of research on the ethics of artificial intelligence. This emphasizes the necessity of principles in ensuring that technologies do not simply exacerbate prejudices or create new societal problems. As stated in the UNESCO draft recommendation on AI ethics:

We need international and national policies and regulatory frameworks to ensure that these emerging technologies benefit humanity as a whole.

Many frameworks and recommendations have been developed in recent years to outline objectives and priorities for ethical AI.

This is unquestionably a positive start. However, when addressing issues of bias or inclusion, it is also necessary to explore beyond technical solutions. Biases can enter at the level of the person who sets the goals and balances the priorities.

In a recent study, we propose that inclusivity and diversity must also be considered when determining ideals and defining frameworks for what constitutes ethical AI. This is especially important given the rise of AI research and machine learning on the African continent.

Africa’s Artificial Intelligence (AI) Context

African countries are investing more in AI and machine learning research and development. Data Science Africa, Data Science Nigeria, and the Deep Learning Indaba with its satellite IndabaX events, which have been held in 27 different African nations so far, demonstrate the interest and people investment in the fields.

A key motivator of this research is the potential of AI and associated technologies to promote prospects for growth, development, and democratization in Africa.

Despite this, very few African voices have been included in the worldwide ethical frameworks that try to guide research. This may not be a problem if the concepts and values embodied in those frameworks are universal. But it’s unclear whether they do.

The European AI4People framework, for example, is a synthesis of six existing ethical frameworks. One of its guiding values is respect for autonomy. Within the applied ethical field of bioethics, this principle has been questioned.

It is considered as failing to do justice to the communitarian values that are shared throughout Africa. These are less concerned with the individual and more concerned with the community, even requiring exceptions to such a concept in order to allow for effective interventions.

Such issues, or even awareness of the possibility of such challenges, are generally absent from discussions and frameworks for ethical AI.

Just as training data can exacerbate existing inequities and injustices, neglecting to understand the existence of multiple sets of values that vary across social, cultural, and political contexts can.

AI systems that are inclusive produce better results

Furthermore, omitting to consider social, cultural, and political settings might result in even the most perfect ethical technical solution being ineffectual or misdirected if implemented.

Any learning system requires access to training data in order to be effective at making relevant predictions. This entails samples of the data of interest: inputs in the form of different features or measurements, and outputs that are the labels that scientists seek to predict.

In most circumstances, both these traits and labels necessitate human understanding of the problem. However, failing to account for the local environment correctly may result in underperforming systems.

Mobile phone call data, for example, have been used to estimate population estimates before and after disasters. Vulnerable groups, on the other hand, are less likely to have access to mobile devices. As a result, this strategy may produce ineffective results.

Similarly, computer vision technology for identifying various types of structures in an area will most certainly underperform when multiple construction materials are employed. In both of these scenarios, as we and other researchers argue in another recent study, failing to account for regional differences can have a significant impact on everything from disaster relief to autonomous system performance.

In the future

AI technologies must not merely exacerbate or absorb the negative characteristics of contemporary human society.

It is critical to be sensitive to and inclusive of various settings while building effective technology solutions. It is also critical not to presume that values are universal. People from various backgrounds must be included in the development of AI, not only in the technical elements of designing data sets and the like, but also in defining the values that can be called upon to frame and set objectives and priorities.