The Rise of Agency Banking in Rural Africa

The bank branch arrived in Chibok, northeastern Nigeria, not as a building but as a person. Grace Musa operates from a wooden kiosk beside the town’s main market, equipped with a point-of-sale terminal, a smartphone, and a lockbox. She processes deposits, withdrawals, and bill payments for farmers, traders, and teachers who would otherwise travel 40 kilometers to reach the nearest brick-and-mortar bank.

This is agency banking, and it has become the primary financial infrastructure in hundreds of rural African communities where traditional banking proved economically unviable.

From Experiment to Essential Infrastructure

Agency banking allows licensed financial institutions to extend services through third-party agents, typically small shop owners, mobile phone vendors, or entrepreneurs who conduct basic transactions on behalf of banks or mobile money providers. The model emerged in Brazil and South Asia before gaining traction in Africa during the late 2010s.

Nigeria’s Central Bank licensed the first bank agents in 2013. Kenya’s M-Pesa had already demonstrated that Africans would embrace non-traditional financial touchpoints, but agency banking offered something mobile money alone could not, and that is cash-in and cash-out services connected directly to conventional bank accounts.

The regulatory frameworks that enabled this shift came from necessity. Banks faced mandatory financial inclusion targets from central banks while confronting the harsh mathematics of rural expansion. Building a branch in a village of 5,000 people costs roughly the same as building one in Lagos or Nairobi, but generates a fraction of the transaction volume. Agency networks provide solutions like lower fixed costs, distributed risk, and the ability to scale quickly into previously unbanked territories.

The Economics Behind Rural Penetration

Agent networks grow where formal infrastructure cannot. In Tanzania, over 1.2 million active agents operated by 2022, far exceeding the country’s branch network. Kenya’s Equity Bank maintains over 42,000 agency points, with the institution capturing significant market share among the country’s commercial bank agents. Nigeria’s ecosystem proved particularly explosive. FirstBank alone reported operating 200,000 agents across 772 of Nigeria’s 774 local government areas by March 2023.

The business model works because agents absorb operational costs that would otherwise fall to banks. Agents pay for their own premises, electricity, and security. They earn commissions on transactions, typically between 0.2% and 1% of transaction value, creating an incentive to process volume. Banks gain transaction fees and deposit growth without fixed-cost expansion.

For rural customers, the value proposition centers on proximity and hours. Agents operate from dawn until evening, often seven days per week. A farmer can deposit proceeds from a morning market sale by afternoon, or a schoolteacher in a remote district can receive salary payments without losing a day’s work to travel.

This convenience has measurably shifted financial behavior. Account ownership in sub-Saharan Africa increased from 34% in 2014 to 58% in 2024, according to the World Bank’s Global Findex Database 2025, with agency banking cited as a primary driver alongside mobile money adoption.

The Regulatory Balancing Act

Governments and central banks across Africa have learned that light regulation accelerates agent growth, but too little oversight invites fraud. Ghana’s Bank of Ghana introduced tiered agent categories in 2022, allowing smaller agents to handle limited transaction values while requiring more robust compliance infrastructure for high-volume operators.

Nigeria’s Central Bank has oscillated between expansion and control. After agent numbers surged past 1.5 million, the CBN in October 2025 imposed stricter registration requirements and mandated transaction limits through new guidelines that take effect in April 2026. The policy aims to curb fraud through measures including a single-principal exclusivity rule, where agents can only work with one financial institution, and daily cash-out limits of 1.2 million naira per agent.

The challenge intensifies in cross-border contexts. The East African Community has worked toward harmonized agent banking regulations since 2021, but implementation remains uneven. A Kenyan agent cannot legally serve a Ugandan customer even in border towns where populations overlap, creating friction in regional commerce.

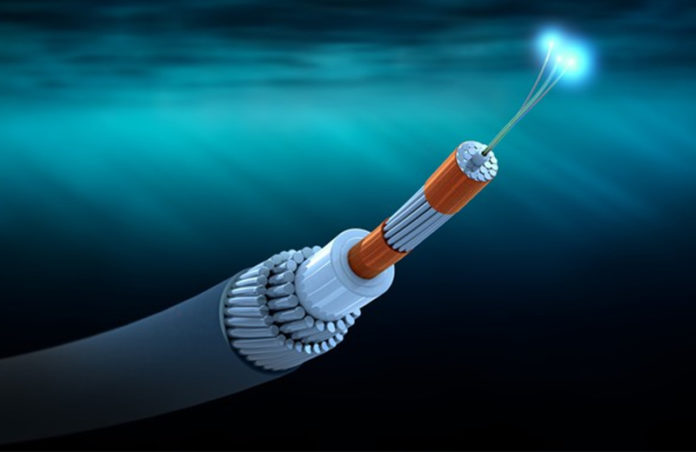

Technology Infrastructure and Digital Literacy Gaps

Agency banking depends on reliable mobile networks and electrical power, resources that remain inconsistent in many rural areas. According to research published on agency banking challenges, agents in northern Ghana and southern Mali frequently report of lost revenue when network outages prevent transaction processing. Some have invested in backup power solutions, but this raises operational costs in already low-margin businesses.

The human element introduces both strength and vulnerability. Agents build trust through personal relationships and local knowledge, often extending informal credit or allowing flexible transaction timing. Yet this same proximity creates exploitation opportunities. Reports of agents charging unauthorized fees or manipulating illiterate customers appear regularly in regulatory complaints across multiple countries.

Financial literacy programs have become essential complements to agent network expansion. Financial literacy rates remain low across many African markets. South Africa reported 42%, Tanzania 40%, Kenya 38%, and Nigeria just 26% according to Standard & Poor’s Global Financial Literacy Survey, making education initiatives critical for safe agent banking adoption.

What the Data Shows About Impact

The numerical evidence of agency banking’s reach has become substantial. The World Bank’s 2025 Global Findex data indicated that 40% of adults in sub-Saharan Africa now have a mobile money account, up from 27% in 2021, with agent-assisted transactions accounting for a significant portion of all formal financial services usage in rural areas.

The gendered dimension of this growth deserves attention. Women in rural areas use agents at higher rates than men. This is partly because agents reduce the time and travel costs associated with financial transactions, constraints that disproportionately affect women managing both income-earning work and domestic responsibilities.

Agricultural value chains have particularly benefited. Farmers increasingly receive payments through agent networks rather than cash from middlemen, reducing theft risk and creating transaction records useful for accessing credit. More than 80 million unbanked adults in sub-Saharan Africa receive payments for agricultural goods in cash, representing a significant opportunity for further digitalization through agency banking channels.

The Path Forward

Agency banking has demonstrated staying power beyond initial pilot enthusiasm. Networks continue expanding, technology continues improving, and regulators continue refining frameworks based on operational experience. The model appears likely to remain Africa’s primary rural financial infrastructure for the foreseeable future, not because it represents technological sophistication but because it matches available resources to actual needs.

The question is no longer whether agency banking works in rural African contexts, as the evidence clearly shows it does. The issue is how to strengthen agent networks against fraud, ensure fair treatment of customers with limited financial literacy, and integrate agency services with digital financial innovations that continue to emerge. These are implementation challenges, not conceptual ones, and they yield to patient regulatory work rather than dramatic policy shifts.