6 reasons why Africa’s new free trade area is a global game changer

• AfCFTA, the largest global free trade area by countries participating, could transform the continent’s economic prospects.

• It aims to be a model of cross-border cooperation in an era of growing isolationism.

• The agreement must overcome implementation challenges to realize its many benefits.

The arrival of COVID-19 in 2020 has rapidly reshaped countries, societies and communities. Our response to the pandemic has changed political and social systems and created new social norms.

Now the world continues to face a plethora of challenges – including climate change, inequality, technological change, migration and displacement – that are both complex and evolving, and which demand collective action.

Most pressingly, the full economic impact of the pandemic is still not fully understood: The IMF projected a historic global GDP contraction of 4.4% in 2020 and a partial and uneven recovery in 2021, with growth at 5.2%.

And yet, despite these challenges, global leadership and cooperation have been woefully lacking since the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis. During this time, our rules-based international order became more fragile and even “disordered”.

We saw a rise of populism, protectionism and nationalism, exacerbated by COVID-19. Citizens’ trust in governments across the world has been eroded, creating fragility in once-stable democracies. Events in the US Capitol last month simply highlight the fragility of the previously thought-to-be-most-stable of democracies.

Enter the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

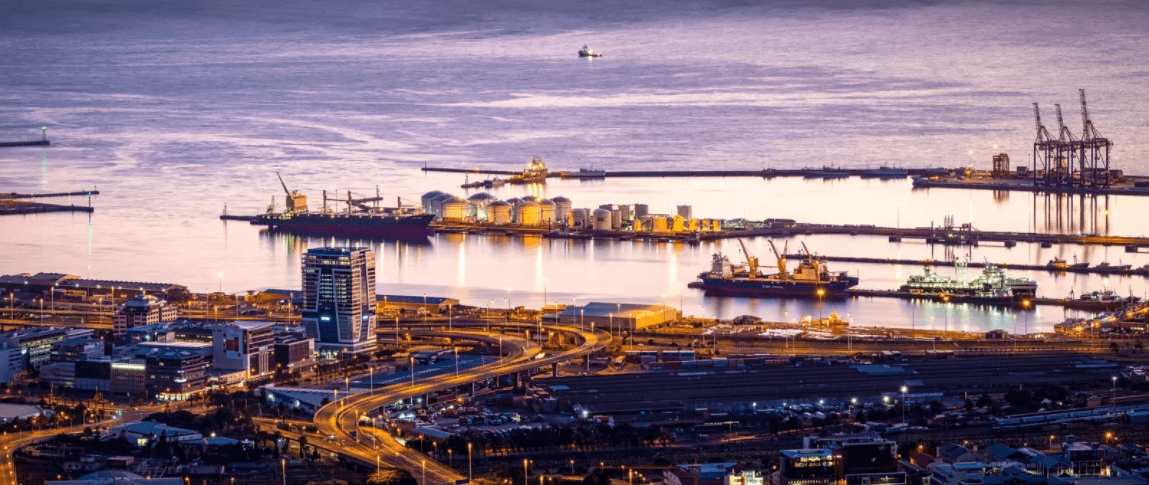

Launched on 1 January, the AfCFTA is an exciting game changer. Currently, Africa accounts for just 2% of global trade. And only 17% of African exports are intra-continental, compared with 59% for Asia and 68% for Europe. The potential for transformation across Africa is therefore significant.

The pact will create the largest free trade area in the world measured by the number of countries participating. Connecting 1.3 billion people across 55 countries with a combined gross domestic product (GDP) valued at $3.4 trillion, the pact comes at a time when much of the world is turning away from cooperation and free trade.

The agreement aims to reduce all trade costs and enable Africa to integrate further into global supply chains – it will eliminate 90% of tariffs, focus on outstanding non-tariff barriers, and create a single market with free movement of goods and services.

Cutting red tape and simplifying customs procedures will bring significant income gains. Beyond trade, the pact also addresses the movement of persons and labour, competition, investment and intellectual property.

To overcome many current challenges, and to build back better in the wake of COVID-19, now is the time for more trade and greater cooperation. If fully implemented, what would this exciting new agreement bring to Africa and to the world?

1. The AfCFTA will significantly reduce poverty

According to a recent report by the World Bank, the pact will boost regional income by 7% or $450 billion, speed up wage growth for women, and lift 30 million people out of extreme poverty by 2035. Wages for both skilled and unskilled workers will also be boosted by 10.3% for unskilled workers, and 9.8% for skilled workers.

The AfCFTA highlights the significant and increasing commitment of the African Union to reducing poverty through trade – a link that is increasingly recognized. As Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, candidate for the WTO Director General, recently stated: “Trade is a force for good, and properly harnessed can help lift millions out of poverty and bring shared prosperity.”

2. Positive economic outcomes will be many and varied

Diversifying exports, accelerating growth, competitively integrating into the global economy, increasing foreign direct investment, increasing employment opportunities and incomes, and broadening economic inclusion are just a few of the positive economic outcomes AfCFTA can bring.

It is estimated that the agreement will increase Africa’s exports by $560 billion, mostly in manufacturing. Intra-continental exports would also increase by 81%, while the increase to non-African countries would be 19%. According to Mo Ibrahim Foundation, if successfully implemented, AfCFTA could generate a combined consumer and business spending of $6.7 trillion by 2030.

Furthermore, markets and economies across the region will be reshaped, leading to the creation of new industries and the expansion of key sectors. Significantly, it would make African countries more competitive globally.

3. Women stand to gain

The AfCFTA clearly focuses on improving the lives of women. There is a risk that some of the economic gains made by women through trade could be reversed by the COVID-19 crisis. According to the Economic Commission for Africa, women account for around 70% of informal cross- border traders in Africa.

Through such work, women can be vulnerable to harassment, violence, confiscation of goods and even imprisonment. Tariff reductions under the AfCFTA will enable informal women traders to operate through formal channels, bringing better protection. Furthermore, a growing manufacturing sector would provide new job opportunities, especially for women.

As AfCFTA Secretary-General Wamkele Mene stated, “It [the AfCFTA] will be the opportunity to close the gender income gap, and the opportunity for SMEs to access new markets”. This is significant, since small and medium-sized enterprises account for 90% of jobs in Africa.

4. Trade integrity will be centre-stage

The AfCFTA offers an opportunity to promote good governance both globally and across Africa, through the concept of “Trade Integrity” – defined as international trade transactions that are legitimate, transparent and properly priced – as a way to ensure the legitimacy the global trading system. The prevalence of illegally-procured or produced goods (for example, illegal mining or fishing, or goods resulting from child or forced labor), misinvoiced trade transactions (i.e. trade fraud) and opacity in most free trade zones strips governments of revenues – needed now more than ever before to assist with the pandemic response, undermines fair labor standards and human rights, and obfuscates who is involved in trade transactions and what goods are being traded, which can facilitate transnational crime.

5. The negative impacts of COVID-19 will be cushioned

The pandemic is expected to cause up to $79 billion in output losses in Africa in 2020. The African Development Bank Group’s African Economic Outlook (AEO) 2020 Supplement estimates that Africa could suffer GDP losses in 2020 between $145.5 billion (baseline) and $189.7 billion (worst case), from the pre-COVID–19 GDP estimates. Further, trade in medical supplies and food has been disrupted. It is being fully recognized across the continent that AfCFTA presents a short-term opportunity for countries to “build back better” and cushion the effects of the pandemic. In the longer-term, the pact will increase the continent’s resilience to future shocks.

6. The benefits of cooperation will set an example for the world

Across the world, countries are questioning trade agreements and economic integration, alongside turning away from global cooperation, leadership and collective action. Political dynamics are driving short termism, polarization and isolationism. Yet our multiple threats demand long-term thinking and greater cooperation – and this is precisely what the AfCTFA represents. While the world turns in one direction, the African Union is moving in the other by deepening ties across the continent.

At the same time, we cannot lose sight of significant challenges that still exist. Three stand out. First is implementation. A recent article by the African Center for Economic Transformation highlights how the agreement will accelerate economic transformation and help Africa “escape the colonial legacy”. They stress, however, that “the devil is in the implementation” and recommend a bottom-up approach, which focuses on national problems that require cross-border solutions such as shared water resources, regional energy markets and highways.

The second is equity. It will be crucial to understand who gains and who loses from the pact. For example, smallholder farmers may lose if there is a focus on large-scale cash-crop farming, which could lead to greater food insecurity and poor nutrition.

The poverty and social impacts therefore need to be tracked across sectors and those who are negatively affected protected until extractive patterns of trade are replaced by robust value chains, value addition, increased interregional integration, greater investment, creating more jobs and increased income.

And third is infrastructure. According to the African Development Bank, Africa’s infrastructure needs are substantial at $130-170 billion a year, with a financing gap between $68-108 billion, driving most countries’ trade outward rather than inward.